Before books, there were ballads

Appalachian ballads carry centuries of tales across mountain ridges and through family memories. Ready to listen in? Here's where to start.

Have you heard Jean Ritchie?

Five-year-old Jean Ritchie knew she wasn't supposed to touch her father's dulcimer. Balis Ritchie had made it clear—none of his fourteen children were to lay a finger on the precious instrument that hung on the wall of their four-room log cabin in Viper, Kentucky. But when the house grew quiet and her parents were busy with chores, Jean would sneak the dulcimer down and pick out "Go Tell Aunt Rhody," teaching herself to play in stolen moments.

By the time her father decided she was old enough for formal lessons, Jean was already accomplished enough that he declared her "a natural born musician." What Balis didn't realize was that music—like the ballads themselves—has a way of finding its path from one generation to the next, even when actively restricted.

This was 1927, and the Ritchie family possessed something more valuable than they knew: a repertoire of over 300 ballads that had traveled from Scotland and Ireland to take root in the Cumberland Mountains. Every evening after supper, the family would gather on their porch for what they called "singing the moon up"—sitting on swings and rocking chairs, sharing songs until the moon crested over the high peaks surrounding their hollow.

Jean Ritchie would grow up to systematically document these family treasures, writing down 300 songs she had learned "from her mother's knee" and becoming one of the most important preservers of Appalachian ballad tradition. But it all started with a curious child and a forbidden dulcimer, proving that the best stories—and the songs that carry them—always find a way to survive.

Appalachia Book Company is currently developing a podcast series, “Blood Roots,” that presents balladry through radio plays and original music recordings. The four-episode podcast will be recorded in front of a live audience in Pikeville, KY on Sept. 26th.

Ballads are story songs

What makes ballads special isn't just their melodies—it's that they're fundamentally about story. These songs are humanity's news reports, therapy sessions, and cautionary tales all rolled into one. They tell us very human stories: how pride can kill, how love goes wrong, how ordinary people face extraordinary choices. Whether based on true events or ancient folklore, ballads capture the kind of stories that people need to tell—and retell.

Which of these stories do you know?

Barbara Allen: The story of a young woman whose pride becomes her downfall—and his. When sweet William dies of unrequited love, Barbara finally realizes what she's lost, but it's too late for both of them.

Pretty Polly: Willie courts young Polly with promises of marriage, then leads her deep into the woods where he's already dug her grave. A chilling story of betrayal that asks: how well do we really know the people we trust?

Lord Thomas and Fair Ellender: Thomas loves fair Ellender, but his mother insists he marry another girl, for her wealth. The wedding becomes a bloodbath when all three discover that love and money make a deadly combination.

John Henry: The ultimate story of man versus machine—a steel-driving man races a steam drill to prove human worth isn't obsolete. He wins the race but dies with his hammer in his hand, asking what progress really costs.

Omie Wise: When Naomi Wise trusted Jonathan Lewis and met him by the river in 1808, she thought they were eloping. Instead, he drowned her. The real murder became a song that's still sung, proving some stories demand to be remembered.

I feel very strongly that the culture of the mountains is just as rich and beautiful and meaningful as any other culture in the world" - Jean Ritchie

A conversation with William Ritter

We spoke with William Ritter, a Mitchell County native and traditional musician, about the enduring power and relevance of Appalachian ballads. William finds his calling in the traditional music and foodways of Mitchell County, North Carolina, where he grew up surrounded by the cultural richness of the mountains. As a fiddler, ballad singer, and seed-saver, William believes deeply that these old ways of living hold essential wisdom for building strong, resilient communities today.

Q: Why do you think Appalachian ballads remain culturally important in our communities today?

A: These old songs connect us to the people that came before us, they reveal our ancestors’ “hopes, fears, and dreams.” There’s more that they have to offer us than just being historically significant relics. These were songs people sang and shared in difficult and trying times. In the aftermath of Hell-ene, we found that these songs could capture and communicate feelings that words and photographs and videos just couldn’t. I know an excellent photographer that was demoralized about his medium because no picture he took could match what it is like to be in the devastation. A “thousand words” was not enough. In Marshall, NC, which was halfway obliterated by the French Broad river, an artist and entrepreneur named Josh Copus owns this amazing restaurant and hotel called Zadie’s Market. He said the only thing that came close to capturing the swirl of emotions and feelings and thoughts he was carrying, was when Sheila Kay Adams sat down in his devastated building and sang one of these old songs. These are often songs of tragedy, but also resilience and defiance in the face of brutal realities. Many people criticize the content of ballads that feature violence against women, for example, but the songs don’t condone violence, they describe it. Very often the women in ballads have agency or push back against the norms of their society and time.

Q: When someone is listening to an Appalachian ballad for the first time, what should they be paying attention to? What are the key elements that make these songs distinctive?

A: First of all, I suggest that listeners close their eyes, or zone out doing something crafty–maybe crochet for example. Really try to follow the story. Don’t look at the performer. Let the narrative play in your mind like a movie. I have heard some of these songs hundreds of times and I still find something new in the lyrics all the time. Often the songs can be fragmentary, so you have to fill in the blanks a bit. To answer the second question, the key element is that ballads are a narrative story. A non-ballad folksong just throws a bunch of verses that may or may not be related together–they may hint at a story. The Ballad just *tells* you the tale. There’s different kinds of ballads, or genres of ballads, but they are united in that they are a narration set to a melody.

Q: You've learned from master tradition bearers like Bobby McMillon and documented musical families in your region. What have these ballad practitioners taught you about storytelling and human experience?

A: Well one reason I am always encouraging people to learn from living breathing singers (or whatever tradition you are interested in), because that experience can shape your life in so many meaningful ways outside of just learning a craft. From Bobby in particular, I learned that the song is more important than accurately singing a piece *just* the way you learned it. He would gently and respectfully tweak song songs–based on his long admiration and knowledge of the genre. Not unlike someone that restores an old rusted out antique car. Some folks look for this purity that’s never really been there. It’s more important that these songs *run* again, even if you need to borrow a verse from another version of the song, or make a rhyme work again. The songs are a living thing, not some artifact. I’m not suggesting just anyone do that though, restoration work takes experience, knowledge, and talent. For example, don’t go fixing up a violin without finding someone that can give you advice and guidance–look at a lot of violin making books, make relationships with folks who do that kind of thing, and your work will be so much better than if you are making it up as you go.

Q: How do you see the relationship between the musical elements of a ballad—the melody, the rhythm—and the story being told?

A: Well, it’s not often the case, but I generally really want a compelling melody when I am committing to learning a song. For instance, there’s a ballad, one of my very favorites called “Fair Annie of Roch Royal.” I love it, but I have put off learning a version of it because it’s been very difficult to find a text with a melody, and many that I have found just don’t match the hope and heartbreak and resolution of that song. I finally have found an excellent text and tune from a woman in West Virginia called Allie Nuzum recorded in the 40s. Most of the melodies I have encountered were really “sing-songy” and just not emotionally appropriate, in my mind. Granted that’s just my opinion, and I don’t know how many ballad singers are that picky about tunes.

Q: For someone interested in exploring Appalachian ballads more deeply, where would you recommend they start?

A: I don’t know who to attribute this phrase to, but sometimes in the field of folklore you’ll hear people talk about “learning from warm hands.” That means learning a tradition from a living person. There’s an incredible wealth of documented and recorded material in private and university collections, or the Library of Congress, and it is amazing these days what you can pull up on Youtube. That’s all wonderful and helpful and important, but I firmly believe that being in community with people that are carrying on these traditions is vital. I understand that not everyone lives in an area where there are still folks carrying on ballad singing (though you may be able to track down folks who knew ballad singers or are related to them and I think it’s important to be in community with them as well). That said, a good place to start would be going to an immersive music-instruction week focused on ballad singing or highlighting ballad singing. Examples of this would be Augusta Heritage Week, the John C. Campbell Folk School, Swannanoa Gathering, to name a few (scholarships are available). My little ballad singing community is in talks about hosting our own ballad focused weekend camp in WNC. I would also offer a word of caution with a lot of the literature associated with ballad singing, since many of the books you will encounter are dated and many of the conclusions of the collectors and folklorists can be problematic or misleading.

Q: What do you think these ballads can teach us about our own lives and communities?

A: Ballads are a mirror into the norms of the societies that created and carried these songs, and I think it’s an important reminder of how far we have come in personal rights and freedoms. Those rights were hard-won. Singing these songs can show us, dear “trad wives” that we don’t want to go backwards.

Q: Can you recommend any ballad events for readers to attend?

A: Outside of the music camps I mentioned earlier, there’s a ballad swap every second Wednesday at Zadie’s Market restaurant in Marshall, NC. It features singers from a family with perhaps the oldest documented and continuous English language ballad singing tradition. There’s also the Lunsford Festival @ Mars Hill University every year that features a lot of ballad singing. We also have ballad singing at the Happy Valley Jamboree, a festival I run Labor Day Weekend. It’s free to attend and there’s a small fee to camp. Beautiful spot on the river and is also the site of the grave of Laura Foster, who was murdered, according to the ballad and the courts, by Tom Dula.

Listen for yourself

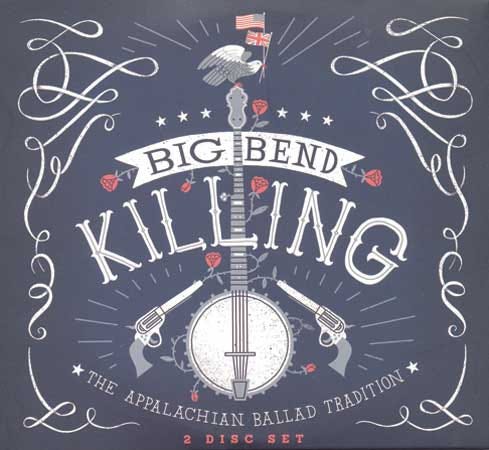

Ted Olson, producer of the Grammy-nominated "Big Bend Killing: The Appalachian Ballad Tradition" and professor of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University, has provided us with a curated list of essential ballad recordings. These selections showcase both the historical depth and contemporary vitality of this tradition.

Contemporary Tradition Bearers

Big Bend Killing: The Appalachian Ballad Tradition - Various Artists (Great Smoky Mountains Association)

This album celebrates Appalachia's rich legacy of songs that tell stories, a tradition traceable to the British Isles, featuring 32 new recordings of traditional ballads by leading UK- and American-roots music luminaries, including Rosanne Cash, Doyle Lawson, Archie Fisher, Alice Gerrard, Sheila Kay Adams, Martin Simpson and othersMy Dearest Dear - Sheila Kay Adams [digital album]

A powerful collection from one of the most important contemporary carriers of the Appalachian ballad traditionRain and Snow - Elizabeth LaPrelle (Old 97 Records)

A young artist's interpretation showing how the ballad tradition continues to inspire new generations

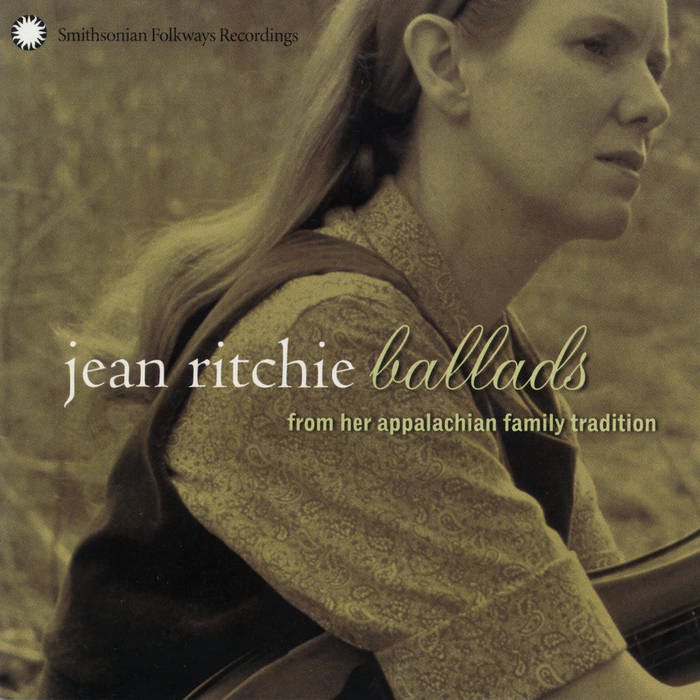

Appalachian Family Traditions

Ballads from Her Appalachian Family Tradition - Jean Ritchie (Smithsonian Folkways)

The legendary Kentucky singer presents ballads passed down through her family, offering an intimate glimpse into how these songs live within mountain familiesFamily Songs and Stories from the North Carolina Mountains - Doug and Jack Wallin (Smithsonian Folkways)

Two brothers from Madison County share their family's musical heritage, demonstrating the living tradition of ballad singing in western North Carolina

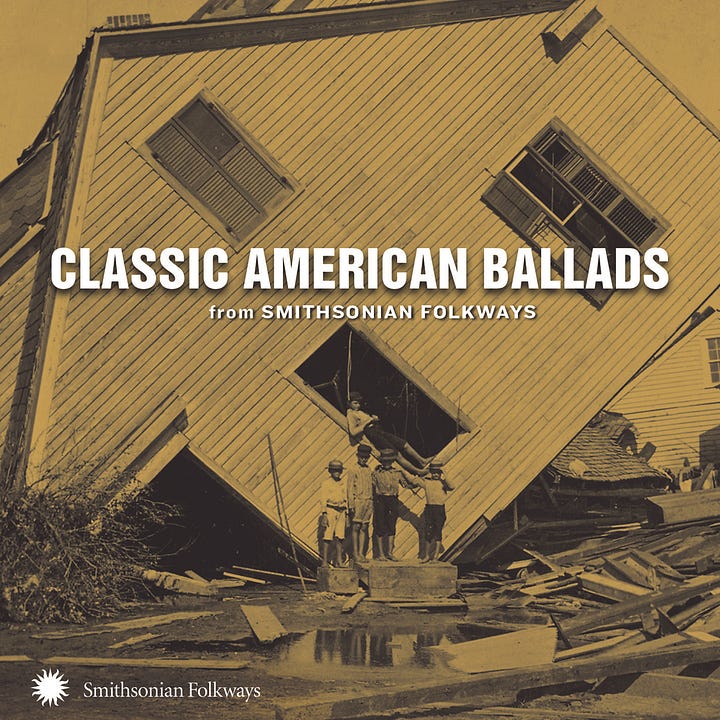

Scholarly Collections

Classic American Ballads from Smithsonian Folkways - Various Artists (Smithsonian Folkways)

An expertly curated anthology that traces the development of ballads in American folk tradition

Connections to Origins

Nothing But Green Willow: The Songs of Mary Sands and Jane Gentry - Martin Simpson and Thomm Jutz (Topic)

A tribute to two important North Carolina ballad singers, highlighting specific traditional repertoiresClassic Scots Ballads - Ewan MacColl with Peggy Seeger (Essential Media Group)

Essential listening for understanding the Scottish roots of many Appalachian balladsBallads: Murder, Intrigue, Love, Discord - Ewan MacColl (Topic Records)

MacColl's masterful interpretations reveal the dramatic power and narrative complexity of traditional ballads

What's your connection to ballad tradition? Did your family sing these old songs? Do you have a favorite ballad or recording we should know about? Drop us a line at hello@appalachiabook.co and tell us more.

Mark your calendars!

Lenoir, NC - Happy Valley Jamboree, August 29-31.

Berea, KY - Appalachian Writers’ Conference, September 2 -4.

Pikeville, KY - “Blood Roots” live recording, September 26th.

Thanks for diving into the world of Appalachian ballads with us! Next month we'll be exploring something completely different. And be sure to like us on Facebook to get the latest about our work!